The "American Period" in New Orleans, which officially began in 1803 with the

Louisiana Purchase but had roots in events stretching into the eighteenth century, brought about tremendous change to the city. It would be easy to characterize this change as taking place slowly, then quickly, but the reality was that some fundamental changes in technology, trade, international politics, and agriculture made things begin to move quite quickly. While I am only forty-two years old, I see American today as being much different than the country in which I spent my childhood. This was definitely true of a New Orleanian at age 42 who might have been born in 1784, during the Spanish period. By 1826, the city would have been notably different than they one that person had been born into.

We need to think about trade routes and their impact upon New Orleans.

France's final defeat in the Seven Year's War led not only to the loss of New Orleans as a colony to Spain, and the loss of Canada to the British (which led to a final diaspora of Acadians to Louisiana), it opened up the Ohio Valley to American colonists. While the British attempted to keep its American colonists out of the area, a literal flood of English-speaking migrants traversed the "Proclamation line of 1763," into the Ohio Valley, the scene of much of the fighting in the French and Indian War. In addition to intense fighting in that region between colonists and Indians, substantial trade ended up working its way down the Ohio River Valley.

|

| A flatboat plying the Ohio River, a vessel capable of going only one way: downstream! |

Interestingly, one legacy of the flatboat trade is the Barge Board House. Here is someone writing about restoring theirs.

|

| Consider the watershed of the Ohio River Valley. How does this connect the Colonial Period's Ohio Valley with New Orleans? |

Once America won its independence and claim to the Ohio Valley, this commerce grew at a greater pace. It is worth noting that the

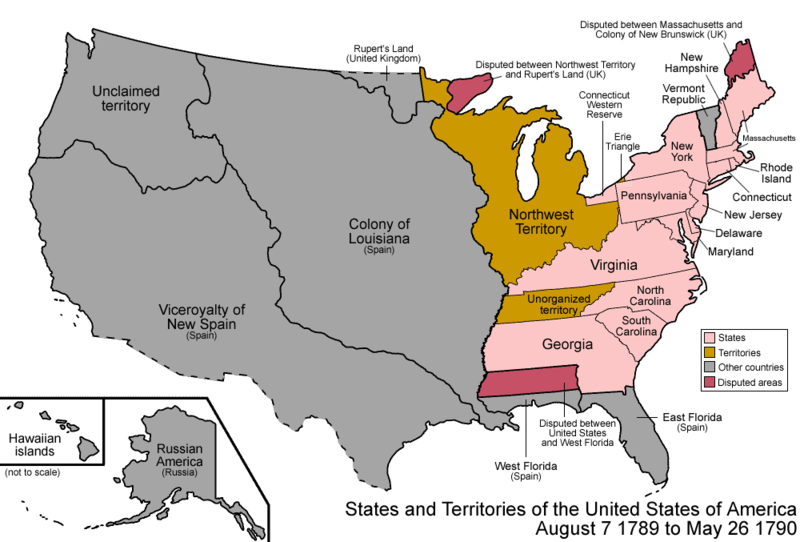

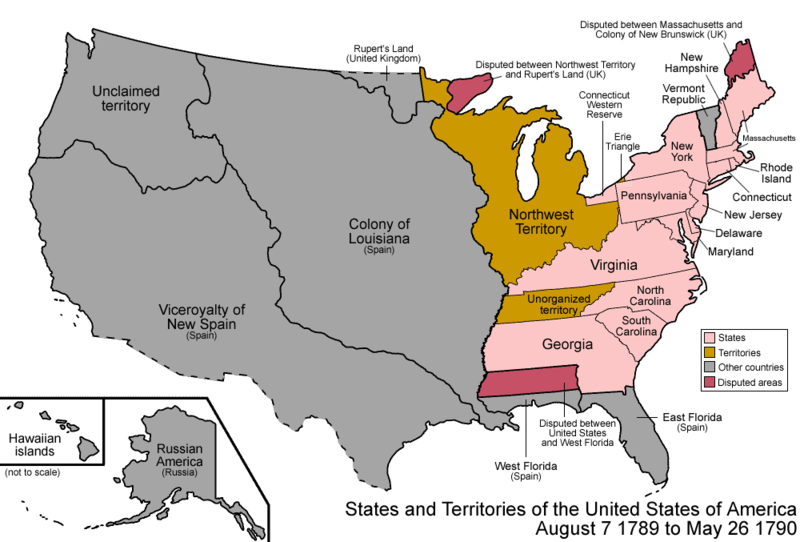

Treaty of San Lorenzo of 1795 was one of the first important moments of diplomacy for the young American government. What did this treaty do and why was it so important? Consider the map below.

|

| a Wikipedia (gasp!) map |

We tend to think of Caribbean nations today as belonging to some sort of "third world" sphere, but in the late 18th Century, they were incredibly profitable slave societies. The effects of the French Revolution reached even San Domingue (Haiti) by spreading revolutionary rhetoric about freedom and the Rights of Man. On an island overwhelmingly populated by slaves, this proved dangerous and led to the Haitian Revolution. Napoleon's efforts to retake the island foundered both from stiff resistance, but also because of severe environmental hazards, particularly

Yellow Fever. The army detailed to re-take Haiti from the rebels was to re-establish control over Louisiana next. With its destruction, Napoleon had lost interest in Louisiana.

The Haitian Revolution also sent its first wave of refugees to Louisiana and the other ports of North America.

The Purchase

|

| A map of the Louisiana Purchase from 1805. Note the potential inherent in the western rivers depicted in this map. (Library of Congress) |

So you can see that it is something of a misnomer to suggest that the "American Period" began distinctly with the 1803 transfer of power. But this did not mean that the switch did not bring big changes!

Agricultural Technology

Two very important technological innovations at the turn of the nineteenth century transformed the agricultural basis of southern Louisiana, and by extension both its profitability as a region and its connection to slavery. The growth of cotton did not really take off until a successful cotton gin became readily available to planters. The sort of fiber one could grow inland was simply too inferior and difficult to process to be profitable. The gin changed all that in 1793.

|

| A model of an "Eli Whitney" style cotton gin |

More of direct import to South Louisiana and the immediate New Orleans agricultural zone was the perfection on the plantation of

Etienne de Boré of a process to granulate sugar from the inferior cane juice produced in Louisiana.

This took place in 1795, and the first truly profitable sugar crop was harvested on lands that now encompass Tulane, Loyola, Audubon Park, and a swath of uptown that made up de Boré's plantation.

Let's think about how this might affect the society that a young William Charles Cole Claiborne had to govern.

|

| W.C.C. Claiborne (La State Museum) |

There were certainly many geopolitical and technological revolutions underway locally and nationally when Claiborne arrived in New Orleans. But it was also a time of enormous international turmoil.

The Haitian Revolution had ramifications for New Orleans beyond its initial phases. When Napoleon launched his

Peninsular War in 1808, deposing the Spanish monarchy, it set into motion a series of irreversible events in the Spanish empire. The most immediate effect on New Orleans

was the eviction of French planters and their slaves who had taken up residence in Cuba during the Haitian Revolution because of their suspected loyalty to France. (You will read about this in Claiborne's letterbooks.

The weakening of Spain precipitated revolution all over Central and South America, but much closer by, it promulgated the

West Florida Rebellion of 1810. (Note, that this was still part of the Spanish Empire!) Mexico's war for independence also began in 1810, beginning a long bloody struggle. In South America, it was now the age of Bolivar and revolution.