Immigrants:

The Irish and Germans were the two largest non-French immigrant groups to come to New Orleans before the Civil War. As it had been for the immigrants who came before them, the reason for their arrival stemmed from problems in the homeland. Poverty and revolution were two recurring themes of this period.

The first significant Irish to come to New Orleans actually did so at the very end of the eighteenth century. These were the "old" Irish. They came in the wake of the failed uprising of the "United Irishmen." Seeking refuge in a Catholic, Spanish New World possession, these arrivals tended to be well educated and/or came from the upper classes. Many would thrive in New Orleans and adopt, ironically, to a slave economy.

Poverty began to drive out the poorer Irish steadily in the 1820s, with the potato blight of the 1840s forming an exclamation point on the migration to the western hemisphere. The

Irish have a memorial in New Orleans at West End, the terminus of what was once the New Basin Canal. The canal was dug in the 1830s to facilitate lakeward commerce. It connected the lake with what is today the location of the Amtrak/Grayhound bus terminal in the Central Business District. The lore is that the Irish dug the canal because they represented a lower cost of labor than slaves. Why might also free laborers be more attractive in the city proper?

|

| Loyola students at St. Alphonsus |

St Patrick's Church, to which you should all make a visit, is a manifestation of the combination of the "old" Irish and "new" Irish, but in reality, really more the "old" Irish. St. Alphonsus in the I

rish Channel is the church of the later, or new Irish. Today, St. Alphonsus is operated as a cultural center.

NOTE: There is an opportunity on Wednesday, March 11, 6 to 8 pm, to go to St. Alphonsus for "fun under the frescoes." This will include Irish Music, Irish Dancing, and alcohol!!!

Check out the Facebook page for it. I will allow you to make up a reading assignment if you shoot a selfie, write a paragraph about your experience.

The "Germans," - really a collection of various Central European peoples, but primarily Germanic nations, fled to New Orleans and elsewhere from political upheaval surrounding the reactionary crackdown against the revolutions of 1848. Like the "old" Irish, this first wave of Germans included many thinkers and professionals. Unlike the "old" Irish, they did not take so fully to the slave system. Theirs was a more evolved form of republicanism. Visiting radicals like the

Hungarian Louis Kossuth helped these migrants stay connected to their homelands. A great many of these Germanic immigrants were also Jewish, strengthening an already significant segment of the New Orleans community. More Germans come later in the 1880s, and we'll talk about them later on in the semester.

Literally across the street from St. Alphonsus, the Germans had their own Catholic church, St. Mary's Assumption.

|

St Mary's Assumption - just right across the street from

St. Alphonsus. The "German" Church. |

|

| A detail from the stained glass in St. Mary's |

Most famously illustrating the role of the German community was the celebrated case of

Sally Miller or Salomé Müller. It was just one of many cases that illustrated the conflicts inherent in the slave system and mixed-race slaves.

Many Germans also settled in what is today considered the Marigny and especially Bywater neighborhoods. Today you can visit what was once the German Holy Trinity Church which operates as the

Marigny Opera House. Attend any of their events and I will allow you to make up a reading assignment. Remember, shoot a selfie, write a paragraph about your experience.

Politics, Politics.

Throughout all of the growth New Orleans witnessed, the municipal boundaries changed a bit, including a

variety of political re-mappings during the nineteenth century, but none were more acrimonious than the

three municipalities of 1836-1847.

Part of the division of the city in 1836 is that the Creoles had begun losing control of the city socially and politically to the immigrants and the Americans, so they wanted to create a portion of the city that they controlled. This meant three sets of courts, three councils, three police departments. It was a real mess. The city reconsolidated in 1852.

When we mean "Creole" by 1836, we must acknowledge in modern parlance that we are talking about white Creole society and Creoles of color.

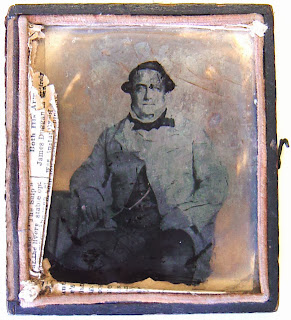

Speaking of Creoles of Color, here is the picture of Edmund Gustave Fortier, the one I told you about in class. The picture dates from the early 1850s. Gustave Fortier is representative of this unusual class in New Orleans. Many were wealthy, most educated or had trades. In fact, specific trades such as shoes, cigars, plaster, masonry, and many butchers were free people of color. Some of you noticed that there were even people of color who owned slaves at this time. We'll talk about that.

At the same time that all of this immigration is happening, making the city seem more like a northern town (it's the only significant site of immigration in the South), economically, New Orleans is becoming more integrated with the region.

This integration has everything to do with agriculture, finance, and slavery. New Orleans will be the hub of cotton and sugar trading and warehousing for the vast Mississippi Valley. Both of these commodities will be extremely profitable in the 1840s and 1850s as textile manufacturing expands rapidly in the North, and in particular, Northeast. Much of the cotton land of the West was still being cleared and planted by southerners who were headed west in search of better land.

New Orleans became the largest slave mart in America, supplying this large westward push with labor. Consider that the Mississippi Delta, some of the richest soil in the world.... WORLD... had mostly not been cleared by the time that the Civil War began.

Lastly, New Orleans became the banking hub of the region, and on the eve of the Civil War, was nearly 170,000 people in size. The next largest southern town was Charleston, and it boasted just over 40,000 people.